Jetpack Compose for Non UI - Tree construction and source code generation

Jepack Compose is two things - a smart tree management solution and a UI toolkit built on top of that tree management solution.

Jake Wharton sums it up well in his article pushing for naming both these components differently and I agree.

What this means is that Compose is, at its core, a general-purpose tool for managing a tree of nodes of any type. Well a “tree of nodes” describes just about anything, and as a result Compose can target just about anything.

Originally built for Android, it has already crossed boundaries into Desktop, Web and recently even command line(!) thanks to Kotlin Multiplatform and tree management abstraction.

While all of them are UI, I wanted to try and explore Compose’s tree management capabilities for a non UI use case.

What we will build?

Code generation is undeniably a common use case in software development and usually done via generation libraries like JavaPoet or KotlinPoet so that we have sufficient type safety and safeguard around corner cases.

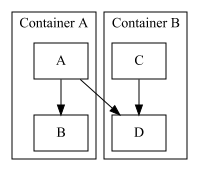

In this article, we utilise Jetpack Compose’s tree management capabilities to generate code for GraphViz’s dot file format. I already have one Kotlin implementation of dot file generation using DSLs in one of my other projects so it lets me draw parallels and compare how Jetpack Compose might help here. A basic understanding on Jetpack Compose would be helpful to the reader.

The final solution might look like below

DirectedGraph("Hello") {

node {

"shape" `=` "rectangle"

}

Cluster("Container A") {

"A" link "B"

}

Cluster("Container B") {

"C" link "D"

}

"A" link "D"

}

that generates the following .dot file.

digraph "Hello" {

node [shape="rectangle"]

"A" -> "D"

subgraph "cluster_Container A" {

graph [label="Container A"]

"A" -> "B"

}

subgraph "cluster_Container B" {

graph [label="Container B"]

"C" -> "D"

}

}

Image generated with dot using the DSL output

Code Generation

Programming language source codes are usually represented as an Abstract Syntax Tree in various phases be it during compilation, IDE support (PSIElement), editing etc. Each node of that tree represents important bits of information like keywords and identifiers etc.

Lets consider the following function

fun sum(a: Int, b: Int): Int {

println("Calculating sum")

return a + b

}

Assuming a Statement interface serving as the tree Node type and respective subclasses for functions, assigment etc, the above can be represented as shown below. Specific details like parantheses are omitted for brevity.

FunctionStatement (sum)

├── FunctionStatement (println)

└── ReturnStatement (return)

└── AssignmentStatement (a + b)

├── IdentifierStatement (a)

├── OperatorStatment (+)

└── IdentifierStatement (b)

Since Compose works so well with construction and managing of trees it should be possible to construct tree of Statements shown above with just @Composable functions and then generate source code with resultant Tree<Statement> that Compose manages.

Jetpack Compose Compiler

Before we jump into implementing such @Composable functions, I want to touch base on Compose Compiler and highlight few behaviors from a non UI point of view. Compose compiler plugin helps in adding/removing/moving tree nodes via pure function calls. For example, consider:

Function¹ {

Function²()

Return()

}

Adds nodes emitted by Function²() and Return() as children to root node Function¹(). This is automatically done without any add() statments, fluent builders or factories with only lexical information thanks to the compiler plugin. Leland Richardson explains why and how in this excellent article.

Applier, Composition and Compose Nodes

Compose has few APIs that allows us to add capabilties to manage tree of any type, let’s go about them one by one.

Applier

The entry point to tree management is the Applier interface which will be used by Compose compiler plugin to modify the tree. We have full freedom to choose the tree implementation of our choice, the Applier abstraction simply gives callbacks at the right places to modify the tree way we want.

A simple implementation of Applier that can add nodes to a tree looks like below.

class Node {

val children = mutableListOf<Node>()

}

class NodeApplier(node: Node) : AbstractApplier<Node>(node) {

override fun onClear() {}

override fun insertBottomUp(index: Int, instance: Node) {}

override fun insertTopDown(index: Int, instance: Node) {

current.children.add(index, instance) // `current` is set to the `Node` that we want to modify.

}

override fun move(from: Int, to: Int, count: Int) {

current.children.move(from, to, count)

}

override fun remove(index: Int, count: Int) {

current.children.remove(index, count)

}

}

Applier is only used to mutate the tree, but we still don’t have a way to connect them with @Composables. Once we have the Applier, we need to create a Composition root so that other @Composable functions can be called. To put it simply, @Composable can be called only inside a @Composable function and Composition function helps in initating the root composition.

Composition

To create a Composition we use fun Composition(applier: Applier<*>, parent: CompositionContext), which takes the applier instance we created above.

To create the root composition:

val composition = Composition(

applier = NodeApplier(node = Node()),

parent = Recomposer(Dispatchers.Main)

)

composition.setContent {

// Composable function calls

}

Notable things here are creating the Applier with root node and passing a Recomposer instance. Recomposer is used for recomposition when the tree changes, since we are dealing with static tree in this article details around it are omitted for brevity but may be covered in a future post.

Once we have the root Composition we have a space to call @Composable functions.

Compose Node

Even though we have a root Composition to call @Composable functions this does not mean that any @Composable can be called here and doing so would result in RuntimeException if the Applier type did not match.

Creating Composable Functions

To place a node in the composition tree, we use ComposeNode function, a @Composable function. It takes the Applier type (should be the same one used in Composition earlier), factory functions and a updator function.

For the Node and NodeApplier the ComposeNode might look like below:

@Composable

fun Root(content: @Composable () -> Unit) {

ComposeNode<Node, NodeApplier>(

factory = { Node() },

update = {},

content = content

)

}

The call site for this function looks like Root {} similar to inbuilt composables. Invoking this function multiple times emits child nodes in the tree at right places.

Google Code sample for managing a generic tree.

Now that we have basic idea of how to connect @Composable function calls to a Tree type, in the remainder of the article we explore how to build dot language composables.

Expressing Dot format as @Composables

In my earlier implementation of DSL, I had basic abstraction root as a DotGraph : Statement interface that can hold a children of Statements. Then extensions functions with infix and trailing lamda allows to build the tree without superflous statements like add() etc.

A digraph "name" {} statement can be abstracted as shown below.

class DotGraph(private val header: String) : Statement() {

private val elements: MutableList<Statement> = mutableListOf()

fun add(statement: Statement) {

elements.add(statement)

}

override fun write(level: Int, writer: PrintWriter) {

indent(level, writer)

writer.println("$header {")

for (element in elements) {

element.write(level + 1, writer)

}

indent(level, writer)

writer.println("}")

}

}

The Statement impls can be anything, even children DotGraphs. I wanted to find a balance between doing everthing in compose vs earlier DSL. For instance, every statement in dot can be a node in the Composition tree similar to ASTs but that meant there will limited control and less flexibility compared to infix functions.

So the balance I settled for was to use Compose to manage a tree of DotGraphs and use traditional recievers to write dot statments like attributes etc into those DotGraph instances.

Without Compose or DSL, the tree can be constructed as follows

DotGraph("digraph \"Hello\"").apply {

add(DotStatement("node").apply {

"shape" `=` "rectangle"

})

add(DotGraph("subgraph \"cluster_Container A\"").apply {

add(DotStatement("graph").apply {

"label" `=` "Container A"

})

add(DotEdge("A", "B"))

})

}

With existing constructs, let’s proceed to see how this can be cleaned up with Compose.

Composition and ComposeNodes

The Applier implementation for DotGraph is left as an excercise for the reader.

As mentioned earlier, I wanted to balance between Compose and traditional Kotlin constructs to add statements. Inspired by existing Compose usage of Scope interfaces to denote a Kotlin lamdba with receivers (DrawScope, BoxScope), I setup a DotGraphScope which can be attached as a Kotlin receiver to @Composable functions. Since every Composable callback will have this instance implicitly, it gives us place to add infix functions and other helpful methods.

@DslMarker

annotation class DotDslScope

@DotDslScope

inline class DotGraphScope(val dotGraph: DotGraph) {

inline operator fun String.invoke(nodeBuilder: DotNode.() -> Unit = {}): String {

dotGraph.add(DotNode(this).apply(nodeBuilder))

return this

}

infix fun String.link(target: String): EdgeBuilder {

val dotEdge = DirectedDotEdge(this, target).also(dotGraph::add)

return EdgeBuilder(dotEdge)

}

// ----

}

I chose to create a DirectedGraph function that will create the root composition instance and provide a @Composable lambda to call other composable functions.

fun DirectedGraph(

name: String,

parent: Recomposer = Recomposer(Dispatchers.Main),

content: @Composable DotGraphScope.() -> Unit

): Pair<DotGraph, Composition> {

val rootDotGraph = DotGraph("digraph ${name.quote}")

val applier = DotStatementApplier(rootDotGraph = rootDotGraph)

val composition = Composition(applier = applier, parent = parent)

composition.setContent {

content(DotGraphScope(rootDotGraph))

}

return applier.root as DotGraph to composition

}

The setContent call kicks off the composition. I should note that it might be useful to retain the Composition instance hence the method returns both the root node of the tree and the Composition.

Graph Composables

Our current intention is to replace add(DotGraph()) with Cluster {} and replace add(DotStatement()) with infix functions, the latter is already done as part of DotGraphScope. As we learnt earlier, adding a node is as simple as a function call, so we could create a cluster composable that emits a ComposeNode of type DotGraph and registers a composable callback for its content.

@Composable

fun SubGraph(name: String, content: @Composable DotGraphScope.() -> Unit) {

val dotGraph = DotGraph("subgraph $name")

ComposeNode<DotGraph, DotStatementApplier>(

factory = { dotGraph },

update = {},

content = {

content(DotGraphScope(dotGraph))

}

)

}

@Composable

fun Cluster(name: String, content: @Composable DotGraphScope.() -> Unit) {

SubGraph("cluster_$name".quote) {

content()

}

}

Ideally the dotGraph should be constructed inside the factory but I cheated there a bit since I needed to use that instance below. This could be explored in a future article when tree mutability is explored.

Results

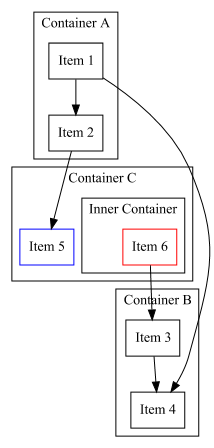

Connecting all together, we have DirectedGraph function to kick start the composition and set of @Composables to construct the source code we intend to generate. Comprehensive example below:

DirectedGraph("Hello") {

node {

"shape" `=` "rectangle"

}

Cluster("Container A") {

"Item 1" link "Item 2"

}

Cluster("Container B") {

"Item 3" link "Item 4"

}

Cluster("Container C") {

"Item 5" {

"color" `=` "blue"

}

Cluster("Inner Container") {

"Item 6" {

"color" `=` "red"

}

}

}

"Item 1" link "Item 4"

"Item 2" link "Item 5"

"Item 6" link "Item 3"

}

and generated image by passing the .dot file to dot:

Image generated with dot using the DSL output

The entire project setup with Gradle and results can be found here.

Compose advantages

DSL can also provide similar functionality of constructing such trees but how does it compare against @Composable functions? There are some key advantages

- As shown above adding, moving and removing nodes are operations supported natively by compose. That means converting node operations to

@Composableautomatically adds those guarantees. For example, instead of custom types to hostadd()functions as shown belowclass Builder { fun node(builder : Node.() -> Unit)) { add(Node().apply(builder)) } }we can create a

@Composable Node()function that has the capabilities automatically generated by compiler plugin. @Composables are just functions. They are not usually hosted inside class types and forces code to be self contained.- Though mutablitity is not covered in this article, it is one of strong features of compose - the ability to do smart updates to tree might be challenging to implement with traditional DSLs. Although possible, it might not be as concise as

@Composablefunctions. - State management. Compose provides property based acces to state and can automatically recompose affected nodes - this can be incredibly useful when needing to modify lot of nodes in response to state changes.

CompositionLocal- Using@Composablefunctions also unlocks several compose specific features likeCompositionLocals. Even though@Composables are static functions, compiler plugin rewrites them into a scope and enables features like state hoisting. Let’s say we have a need to transfer some information from parent nodes to children nodes. Using CompositionLocal we can implicitly share this state while retaining benefits of stand alone static functions.val RootGraphScope = compositionLocalOf<DotGraphScope> { error("Not set") } DirectedGraph("Hello") { CompositionLocalProvider(RootGraphScope provides this) { node { "shape" `=` "rectangle" } Cluster("Inner Container") { RootGraphScope.current.graph { // access parent scope from children "color" `=` "red" } } } }Here through use of

CompositionLocals it should be possible for childrent to access state from parents. It happens behind the scenes without changing the function signature.

Future work

While the current solution explores basic tree management, there are still plethora of things I want to explore further like async with coroutines, tree mutation, recompostion and parallel composition etc. Code generation might not be an exact fit for those things though.

Additionally, Compose has concept of Modifiers to add additional node attributes. For example shape = rectangle for dot node could be a Modifier instead but I chose to avoid it since I wanted to retain ability to add any type of attribute with less code. But still Modifier is a valid usecase and I intend to explore them further.

Would be glad to hear any feedback/concerns in the comments below, thanks.

– Arun

Comments